GOTHIC

Contribution to ‘Quarantaine, My Dear’ icw. Bart Decroos, 2020

![]()

A story by Bart Decroos and Marius Grootveld

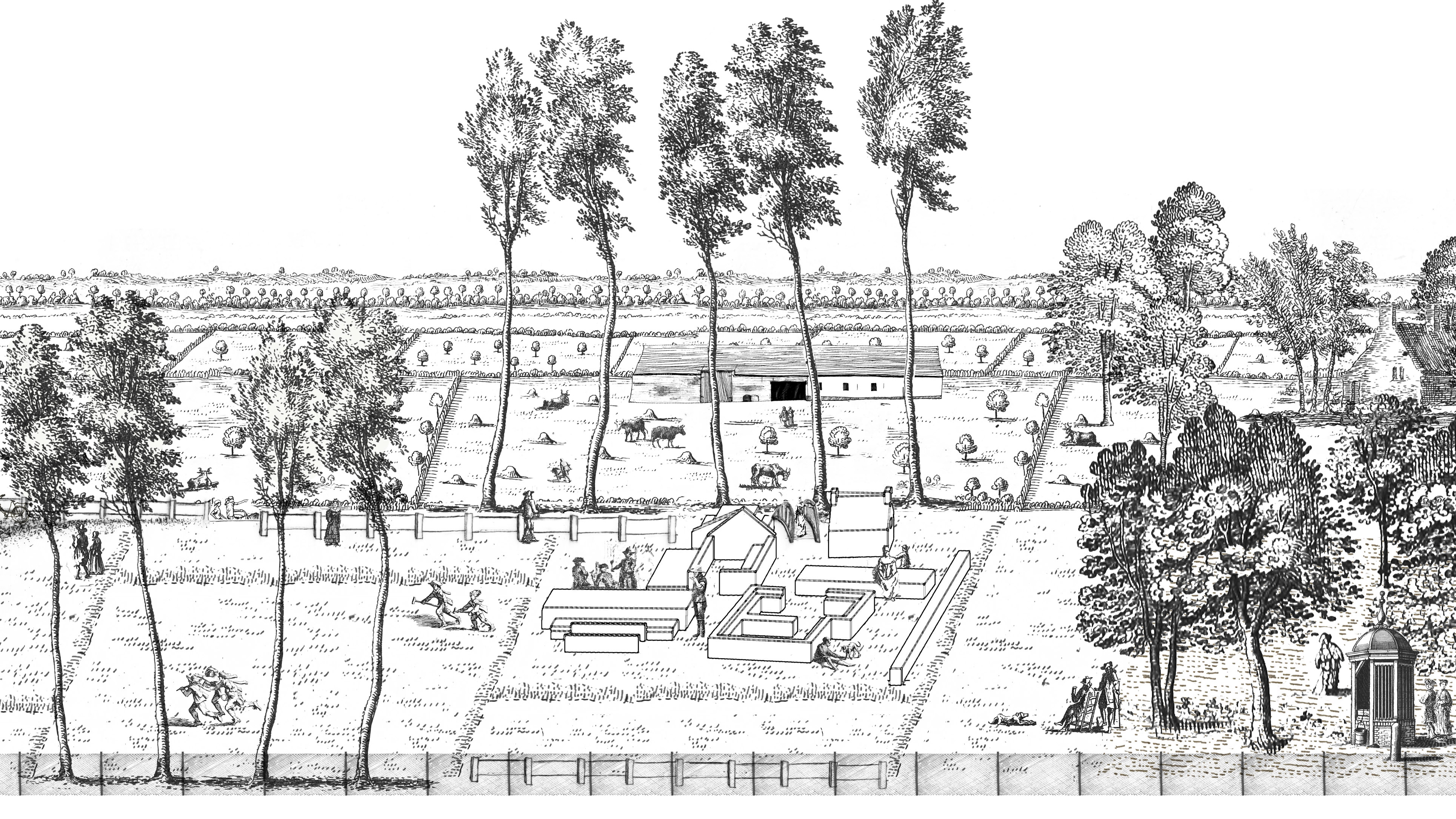

The corridor consisted out of a long sequence of rooms, with doorways lined up in the middle of the walls, to give a view of over thirty or forty rooms far. When someone crossed the corridor, you could see their silhouette passing through the perspectival construction from at least twenty rooms away, on a clear day maybe even twenty-five, thirty. The rooms hadn’t always been connected like this. They had been normal rooms, separate and closed, three or four connected most of the time, depending on the situation. They had belonged to separate houses, offices, restaurants and bars, supermarkets, clothing shops and warehouses. There had been streets between them, squares, parks and alleys. They had been as in any other city, yet, as in any other city, the market value of a square metre had sky-rocketed as a result of profit-driven speculation and the government had gradually been made to realise how economically unsustainable it was to keep so much open space for a public that didn’t own it. The only possibility to lower housing costs and rent fees had been to put more and more open space on the market, allowing the construction of row after row of houses, shops, offices and tower buildings, one after the other in whatever open space the city still had at its disposal—until it ran out.

*

It is easy to imagine how K., that famous character from a Kafka novel, would inhabit such a spatial construction. He would wake up as any other day, in the room he rented from a large corporation. He would get dressed in front of the old woman who lived next doors and whose kitchen window looked out into his room. As usual, she would already be awake and up and about, trying hard not to look at K. Ever since the densification of the city, the social code of its inhabitants had changed into a mutual denial of each other’s presence, as an attempt to keep the illusion of privacy intact. Over the years, K. had filed numerous requests at the local municipality to receive permission for putting up drapes. The requests were filled with reasonable arguments about why the lack of curtains was an infringement on his privacy, to which this or that government official (they were never the same) would reply that it would equally be an infringement on his neighbours’ right to a view and that the status quo would be maintained.

Finally dressed, K. crossed into Mrs. Grubach’s living room next door, which he could use at the times she wasn’t home. Their arrangement gave K. a little more space to live, while the extra rent was a welcome contribution to Mrs. Grubach’s pension. It had taken some time to adjust their respective schedules, but as it was now, K. usually had the opportunity to take breakfast shortly after waking up. Mrs. Grubach’s living room was over-filled with furniture, tablecloths, porcelain and photographs, which she had increasingly gathered in this single room as she had sold off the other parts of her house to project developers and real estate agents. The door on the other side of the living room now led to her former kitchen, which had been transformed into a kind of vestibule for an office space. The simple, square room still contained the built-in stove and cupboards along one side, while the wall on the other side had been torn down to make space for multiple rows of office desks: the dated wallpaper abruptly transitioned into floor-to-ceiling windows, typical of tower façades; the stucco ceiling with a modest chandelier disappeared out of view behind a suspended ceiling system, which started with a few grey tiles here and there but gradually filled up the entire grid above the desks; and the terra cotta floor tiles lined up with a dark, anonymous carpet stretching out to the other end. The desks were deserted, a remnant of an earlier time before most companies had switched to teleworking from home. Mrs. Grubach and K. had taken the liberty of re-claiming the kitchen again to prepare food, as long as no new tenants occupied the space.

This morning, however, K. had no time for breakfast and ran past the desks to the next door on the other side. He was in a hurry.

*

‘Good morning,’ the employee behind the desk said.

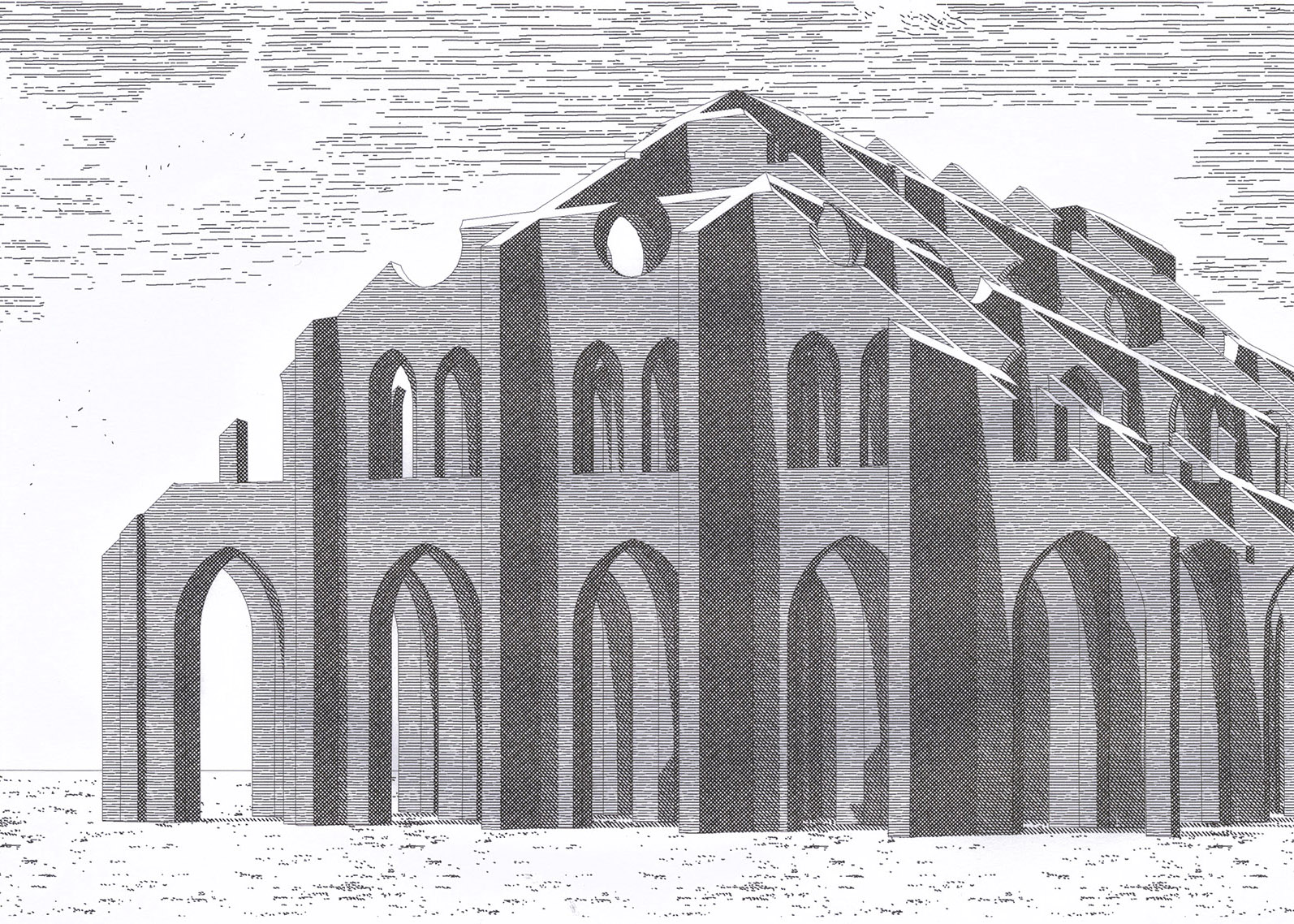

K. stood in the entrance hall of a private bank. In front of him, a row of counter desks was placed on a stretch of marble tiles, while above him, he could see the columns and arches of what he remembered as the central hall of the city’s former train station. He wasn’t sure anymore whether the bank had moved into the train station, or whether the train station had been bought up and replaced to become the decor of the bank. It didn’t really matter.

‘I’m looking for data on this transaction,’ K. said, and he gave the employee a copy of the sales agreement of his parental house.

The house had been sold years before, when his parents needed the money to pay for their monthly bills at the nursing home. The economic logic in which children were also an investment in one’s retirement plan had been rendered obsolete, the wages had simply fallen too low nowadays. And as with most properties in the inner city, the house had first been subdivided into different apartments, and later, when a bunch of start-ups had invented a market for architectural fragments of historical buildings, the house had been cut apart and the decorated ceilings, the hard-wooden floors, the granite façades and all of the neo-classical ornaments had been sold by the pound. A form of recycling that was not as much postmodern as it was economic: it had become cheaper to transport existing craftsmanship than to find artisans to produce new work—if they could still be found, that is.

‘You’re in luck,’ the employee said while looking at his computer screen, ‘most of it has been bought up by the same private party.’

Such transactions used to be registered by the government, but as the public’s distrust of the government grew, entire databases were sold off to private data storages to keep them safe, anonymously. Until, of course, they realised there was a market for it, in which any data could be sold to the highest bidder. Ironic how a thoroughly privatised world could lose any sense of real privacy.

The employee named a price, somewhere near K.’s latest pay check, but what else could he do, he thought. He paid with his card and received a paper slip with geographical coordinates. Addresses had become obsolete as well: places only existed in their geographical location, which at least remained constant in this endlessly changing world of rooms and corridors.

*

K. followed the blue line on the screen of his phone, which showed the route throughout the dense urban fabric. The coordinates indicated a location not too far from where the parental house had been, a district he had not visited in years. The disappearance of the physical place where he had grown up with his brothers and sisters had undermined the already fleeting contact they still had. As far as he knew, they had all found their own room in other parts of the city, rendered into atomised individuals without family ties or defined social circle.

The blue line ran underneath the remnants of a large bridge and up a displaced escalator leading to another level.

Perhaps it was old age, perhaps it was caprice, or perhaps it was something more fundamental that had given K. the idea to track the fragments of the house. Although he knew there was nothing there to be found for him, that whatever may be left was nothing but pieces of brick, of wood, of plaster and paint, he still couldn’t help but believe them to be meaningful.

At the end of a long corridor, after walking through numerous rooms where people went about their business as if a stranger wasn’t passing by, the blue line stopped in front of a wooden door.

The house stood somewhat hidden, awkwardly placed between a row of steel columns and the bell tower of a former church. Its façades were made of concrete, grey planes trying to resist any traces of age. Yet, the door was the very same door he remembered, which had once been painted dark blue but which you could only still see in the folds of the sculpted wood where the remaining paint had not yet flaked off. On the side, K. recognised the bay window, extending outwards with painted glass windows that would light up the living room on sunny days. And although the house was a mere concrete box, seemingly an expression of both economic and ideological poverty, the roof was lined with the very same corniche as his parental home, somewhat out of place now, but an elegant refinement, nonetheless.

K. had not expected to really recognise anything, much less to feel anything—such naive idealism belonged in his youth, he thought. Yet, the wooden door handle still fit his hand, as if the worn out shape adjusted itself to the folds of his skin. Without knocking or ringing, K. turned back and walked down the corridor he came from. Indeed, there was nothing left here for him, but he understood now that others had found their home within the fragments of his youth, and he realised that still others would come after them.

It gave him hope.

PUBLICATION: Quarantaine, My Dear

EDITOR: Jan de Vylder

YEAR: 2021

VELDWERK TEAM: Marius Grootveld

PUBLICATION: Quarantaine, My Dear

EDITOR: Jan de Vylder

YEAR: 2021

VELDWERK TEAM: Marius Grootveld