MOBY DICK, A FISHERY DEPOT

icw. Dyvik Kahlen & Jan Minne, Oostduinkerke, 2019

The National Fisheries Museum in Koksijde is like a richly pictorial theatre stage. It offers a rich representation of the lives of ship builders, coopers, sail makers, line turners and salt mariners, telling the history of Belgian fishing tradition in miraculous stories. Revealed through impressive set pieces, reconstructed interiors and authentic relics such as manuscripts, maps and ship models, visitors are immersed in interiors from the lives of the fishermen, over polyester beaches along a moored barge on foamy water to an underwater world encapsulated within large aquariums. The possibilities of the displays as a museographic tool are taken to the extreme here, bringing together all the essential facets of fishing.

![]()

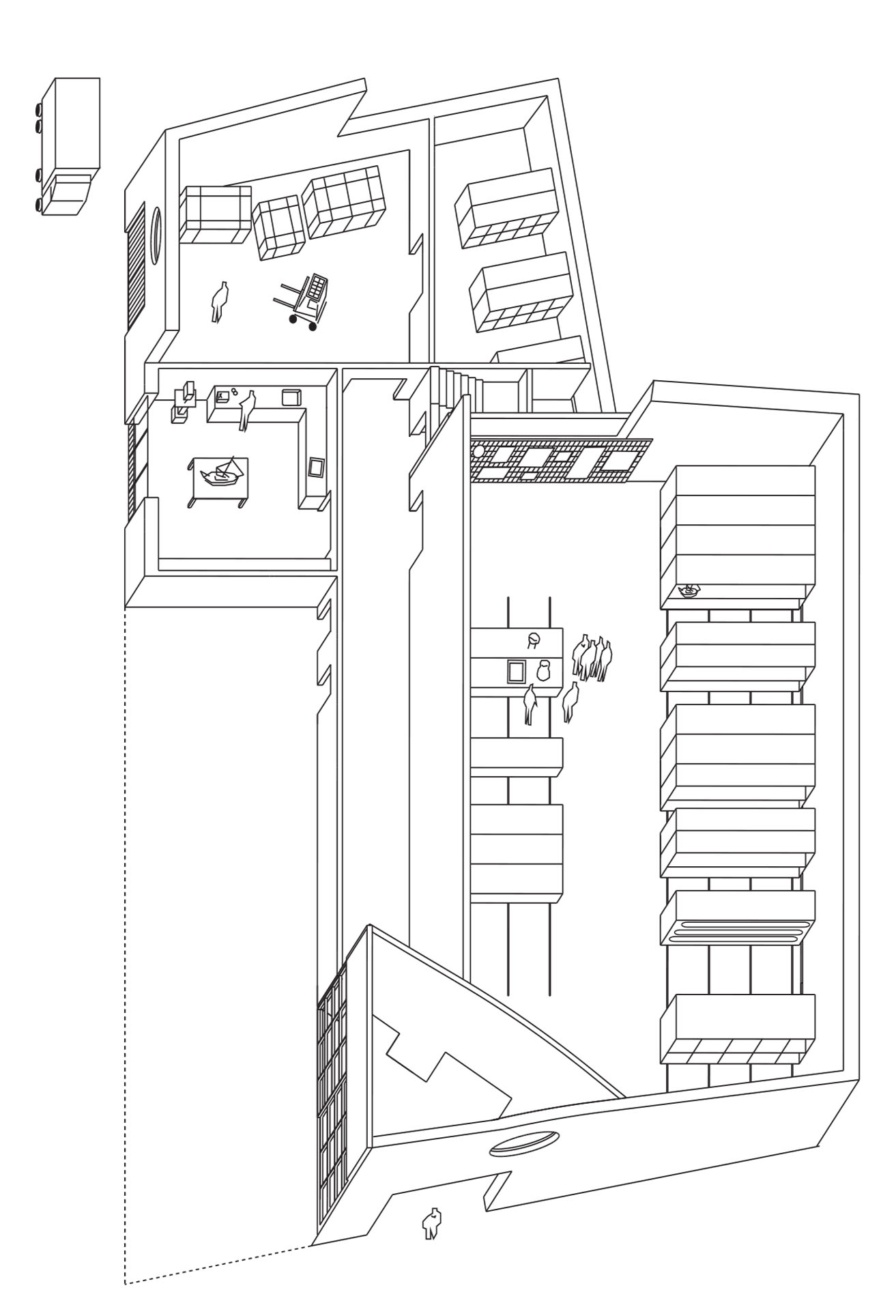

Yet, the artificial pieces on display are merely a representation of reality. Just like in the theatre, reality can only be found behind the scenes. Far from the museum displays, the latest discoveries are made in the research lab and original historical artefacts are packed away at high density at the depot. The functional cabinets that we find here couldn’t be of greater contrast with visual spectacle of the museum spaces.

![]()

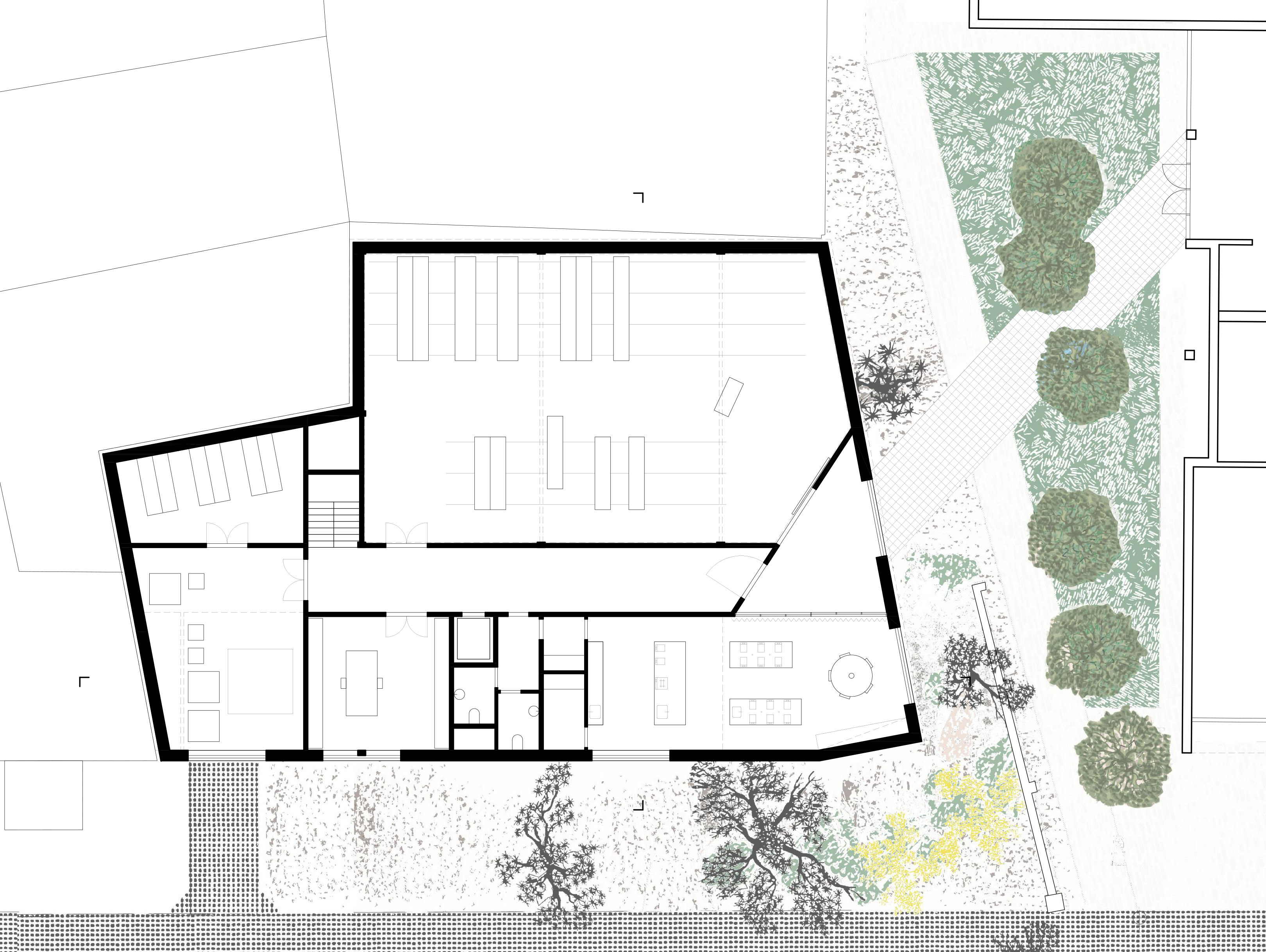

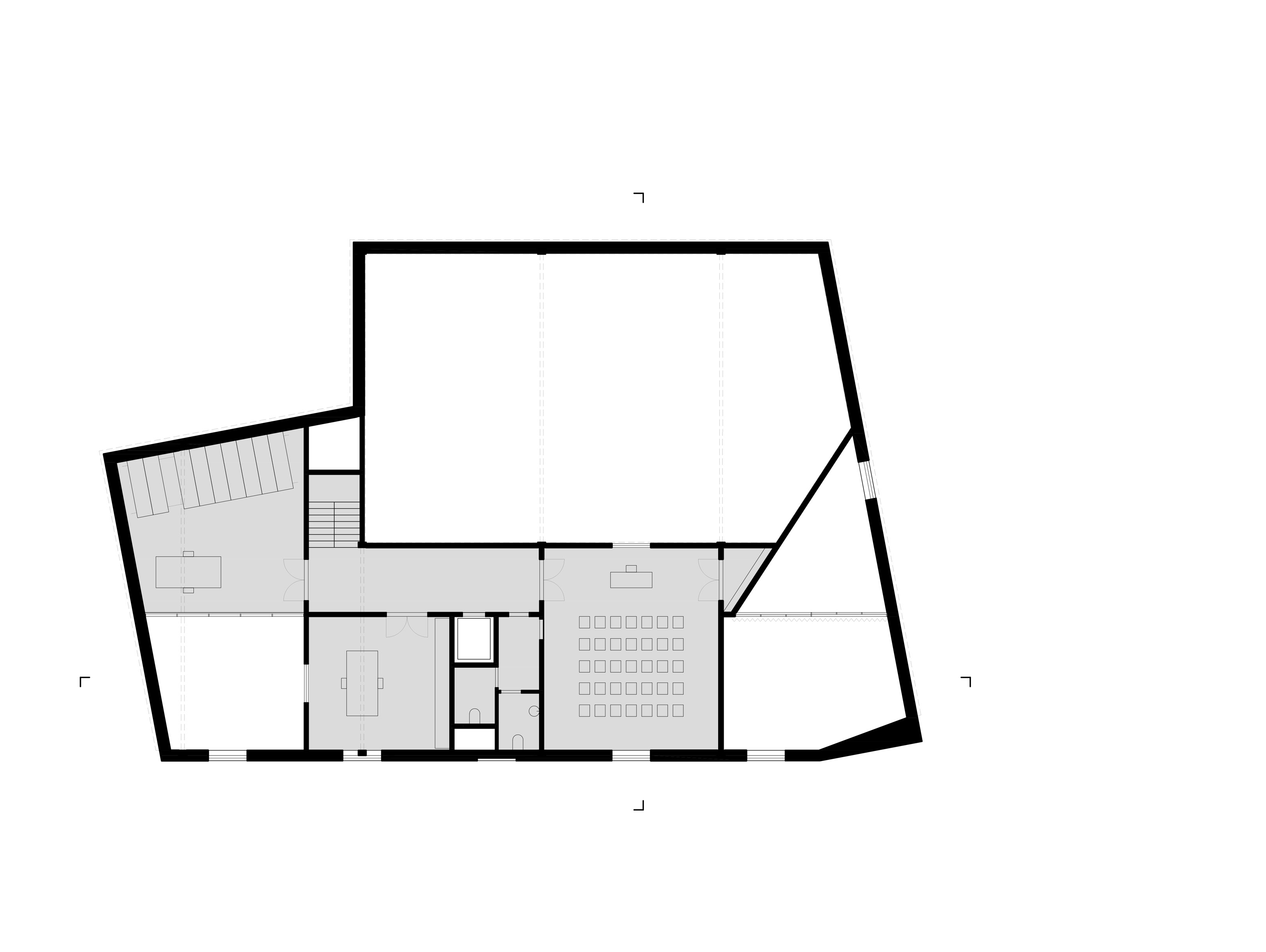

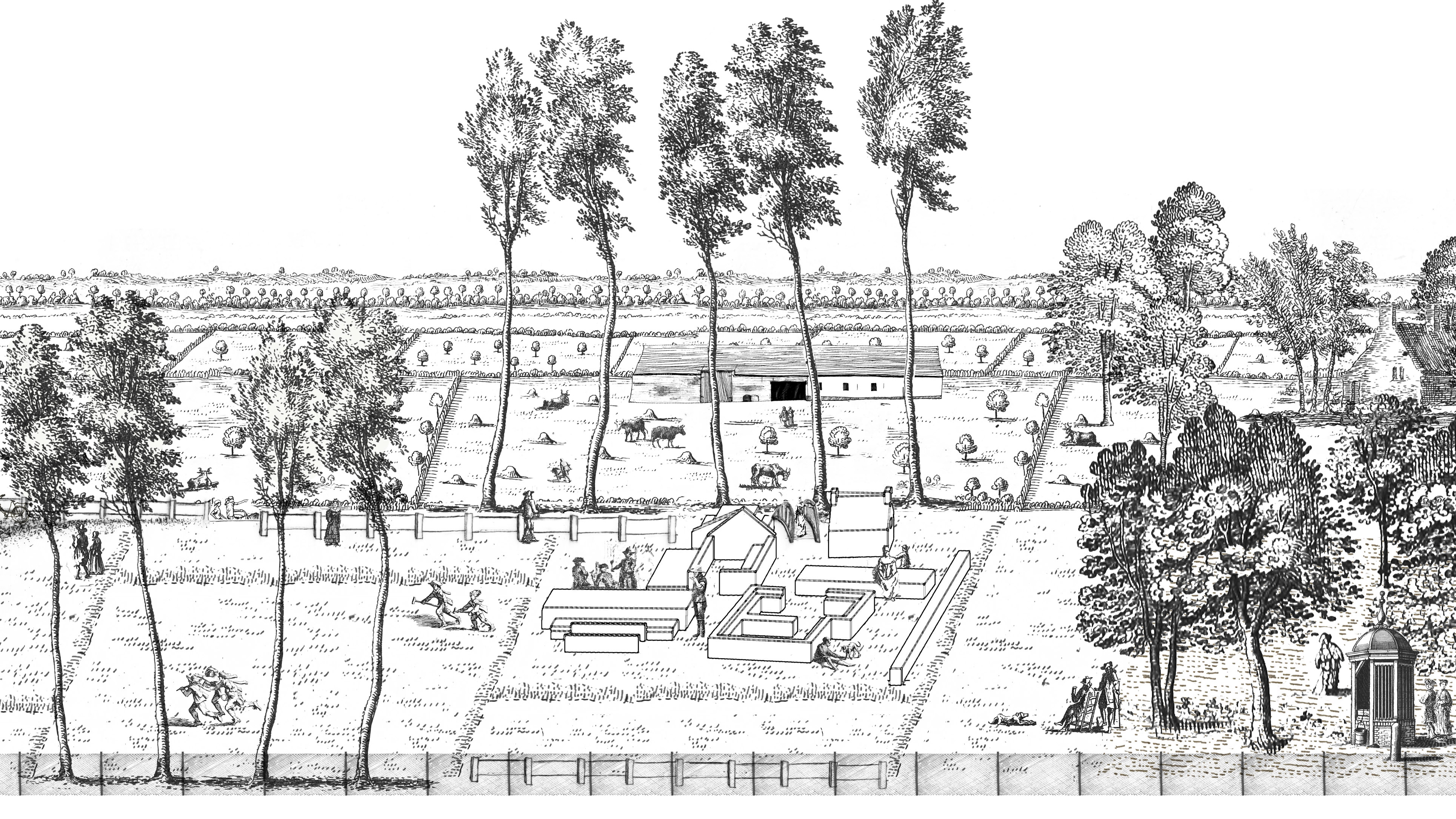

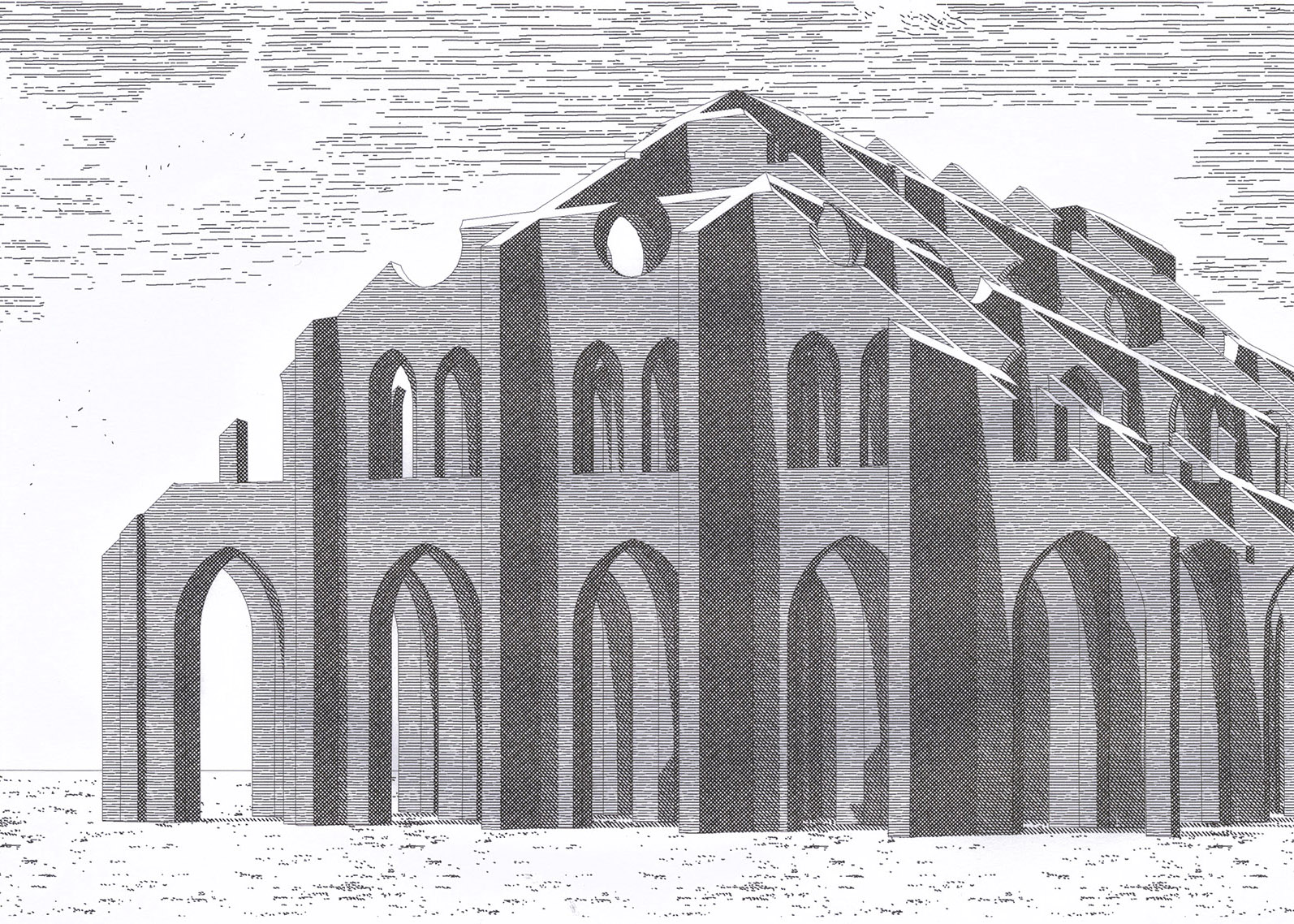

The new depot design initially presents itself as a simple storage shed. The clear construction therefore results in an easy to build and affordable project. It finds its uniqueness in a maritime memory, finding subtle similarities with shipbuilding in several instances; a rhythm of round windows as portholes, a curved facade like a ship's mirror, a chimney reminiscent of a cruise liner, a covered connection as a gangway and a roof construction like a reversed ship. From an urban point of view, the depot building, with its size, also brings the same visual tranquillity in its messy context as a ship in a shipyard. The search for references never becomes childish because the project remains a building in the first place; never a prop.

![]()

![]()

The depot is deliberately restrained on approach, it is a secondary building after all. Functional windows bring light and visibility into the building, but at no point recall a public entrance; this is clearly a facade to walk along. Its only urban function is to introduce the museum further down the road. The red in the facade and its proportions are in a way a prelude for what is to come. To enhance the landscape it was also decided to give the long facade more space and light by transplanting a number of trees. New solitary sculptural pine trees are planted in a picturesque way that together guard the building.

![]()

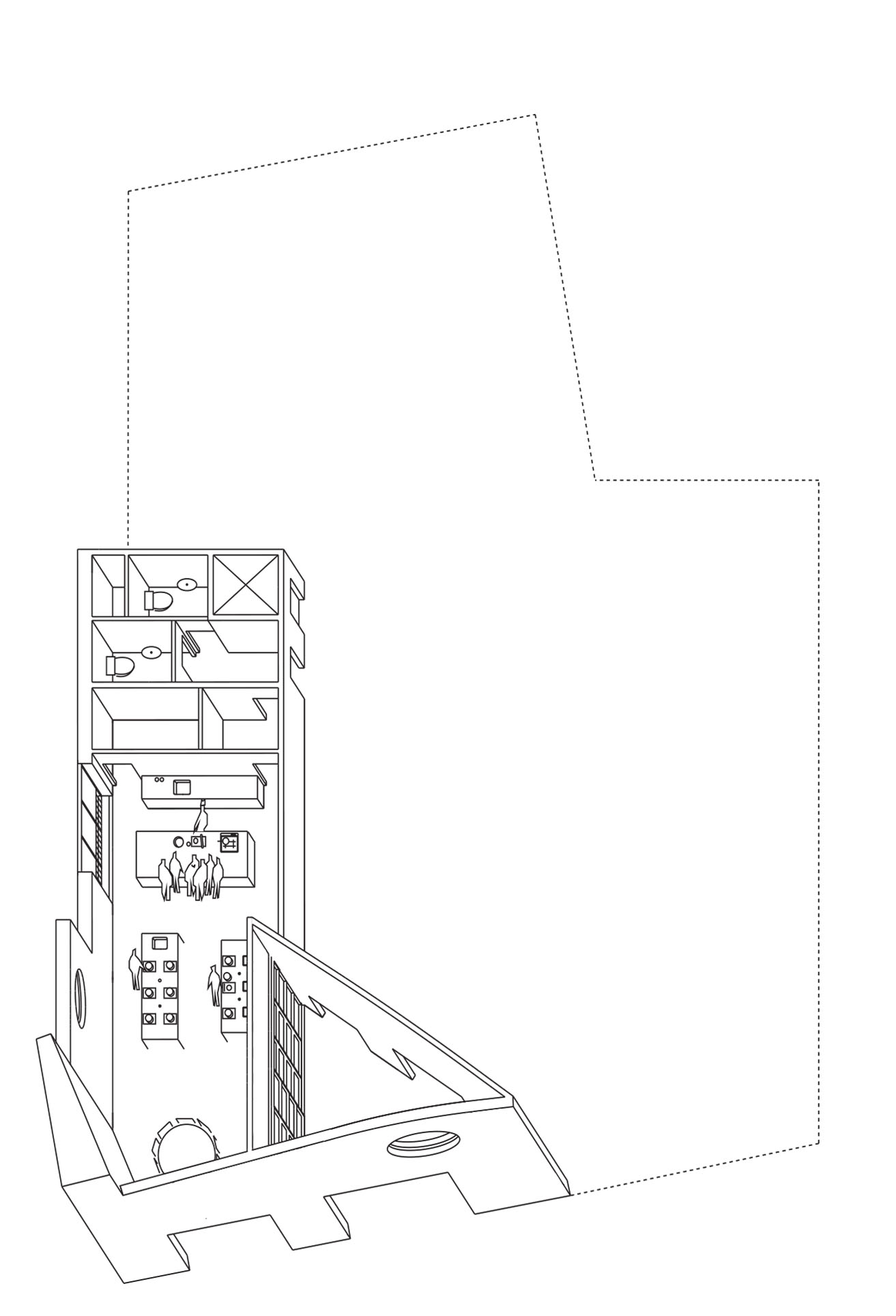

Presenting itself as a grand gesture at the corner, the facade and chimney fold back to increase the view to the museum. Where previously it hid, now every passer-by is made aware of this cultural quarter. Turning around this accentuated corner we find the entrance to the depot. A glazed white facade brings extra light into a more narrow green court and a covered walkway leads visitors into the depot.

![]()

![]()

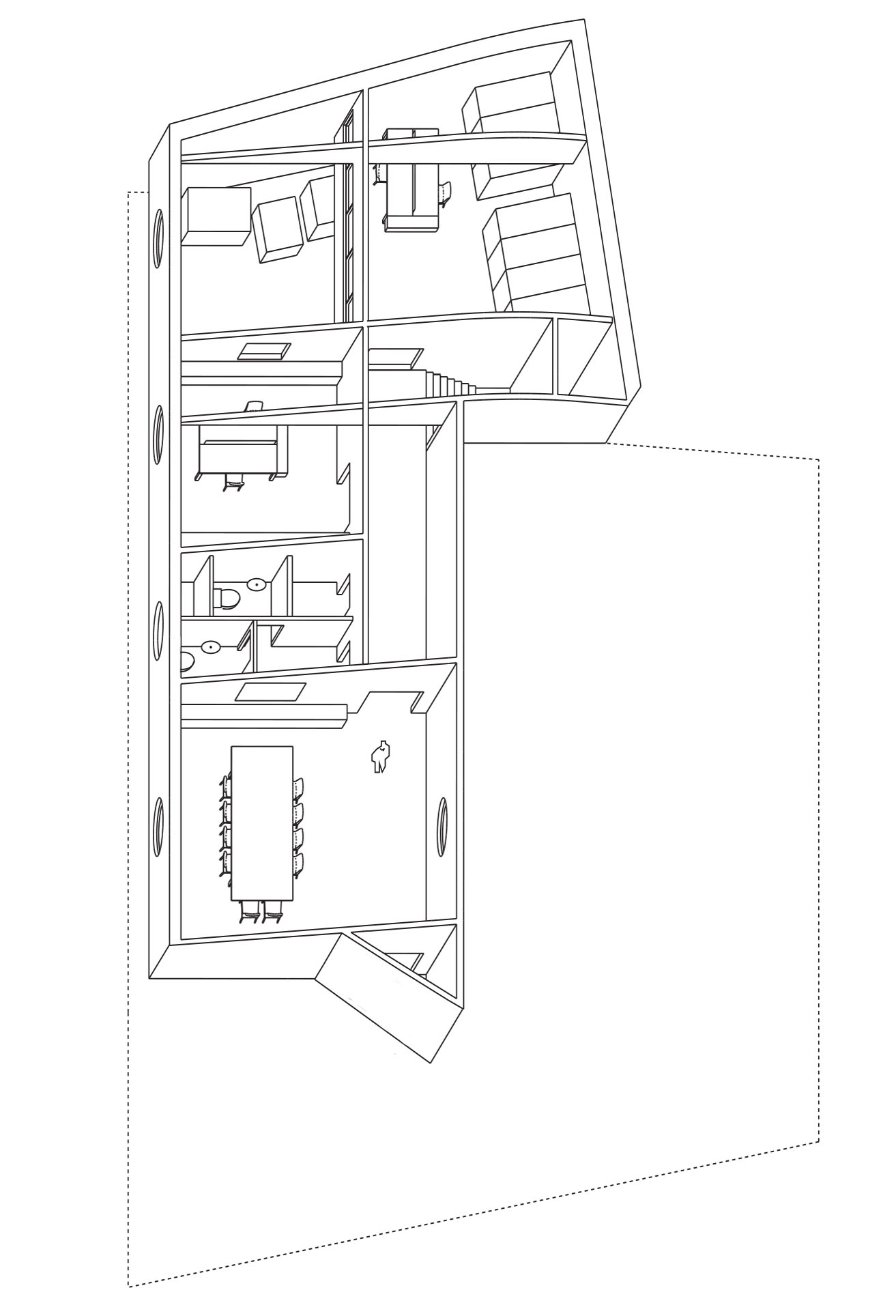

The triangular entrance hall of the building clearly presents its three functions ![]() . A glass wall marks the demonstration kitchen serving to store the immaterial fishery heritage. A white wall with a relatively small door leads to the serving rooms. A bare cinder block wall holding a large red sectional gate leads to the depot which stores the material artefacts of this fishery heritage. In one moment, the entrance explains the building and its functions.

. A glass wall marks the demonstration kitchen serving to store the immaterial fishery heritage. A white wall with a relatively small door leads to the serving rooms. A bare cinder block wall holding a large red sectional gate leads to the depot which stores the material artefacts of this fishery heritage. In one moment, the entrance explains the building and its functions.

![]()

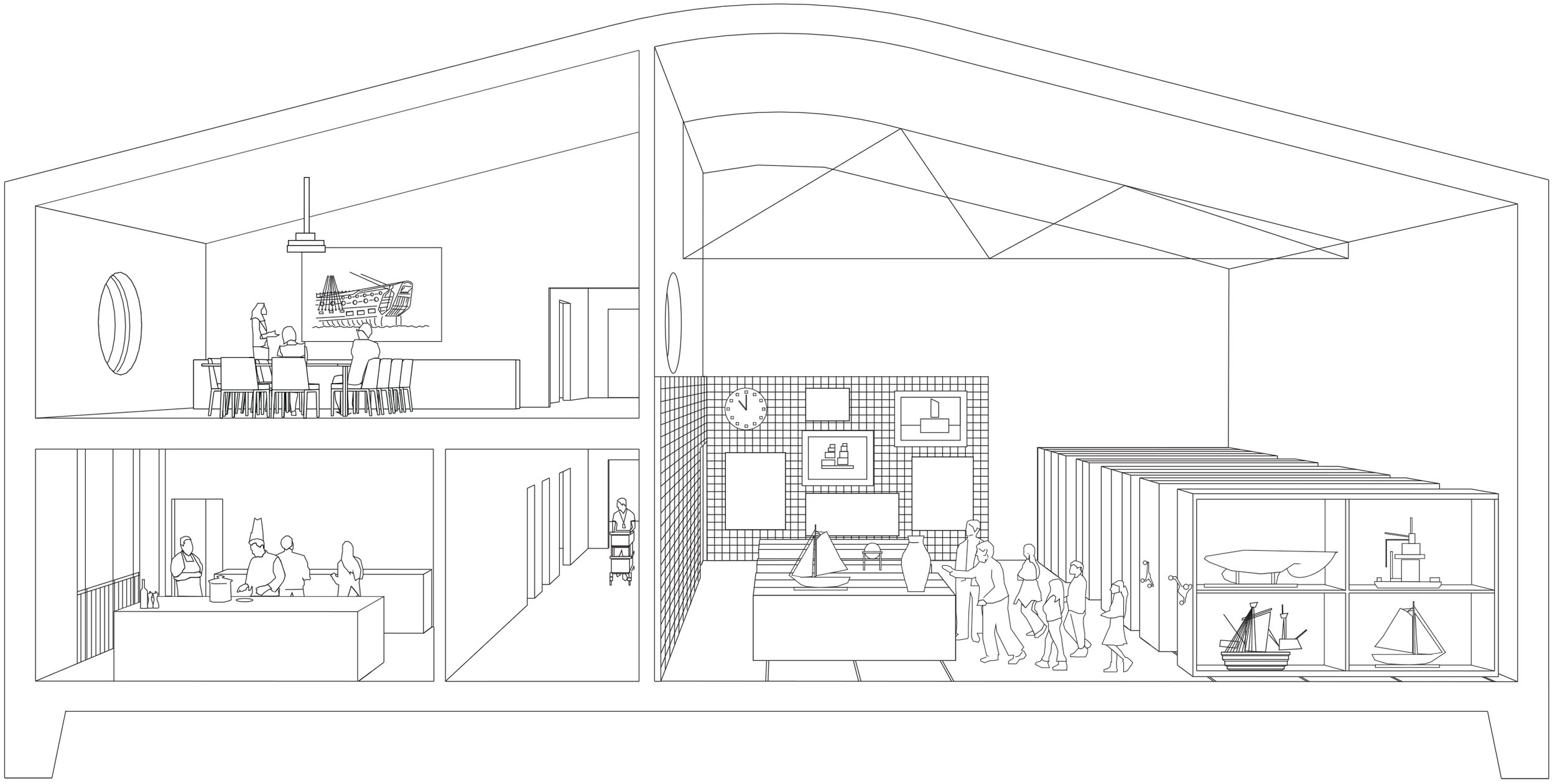

The large door to the depot leads the visitor to a functional rectangular hall with a wealth of utilitarian white depot furniture. When the door opens, there is a visual connection between the depot space and the green gardens outside. The archive pieces briefly make contact with the world they once inhabited and visitors understand that the objects once played a role in history. In this way, the depot makes an essential distinction from other contemporary depots where these pieces from the past are always hidden behind many layers and never come into contact with the present.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The depot and the kitchen both look onto the cemetery wall with a narrow garden in front. The view reads like a series of layers that merge the moments between the museum and the depot. Successively one looks out onto a shallow garden, a green island within it, the brown brick cemetery wall, the row of chestnuts behind and the red facade of the fishing museum. The shallow garden is designed as a narrow strait with rocks as a metaphor for dunes and miniature landscapes as archipelagos or rafts. Here, a garden offers plenty of space for personal imagination, allowing visitors to experience the blurring of the boundaries of the private and public worlds in a very intense way. This garden is a surprisingly versatile universe, composed within the existing framework while undergoing a far-reaching metamorphosis.

![]()

![]()

ARCHITECTURE: Veldwerk Architecten, Ghent icw. Dyvik Kahlen, London

LANDSCAPING: Jan Minne, Brussels

STRUCTURE: Guy Mouton, Ghent

INSTALLATIONS: E-Norm, Ypres

CLIENT: Municipality Koksijde

LOCATION: Oost Duinkerke

YEAR: 2019

BUDGET: € 1 500 000,-

STATUS: Closed Competition, 2nd Place

VELDWERK TEAM: Marius Grootveld, Jazmin Charalambous